With sacred poetry, Robert Bly’s visit draws 300 to UNCA

Tuesday, 01 May 2007

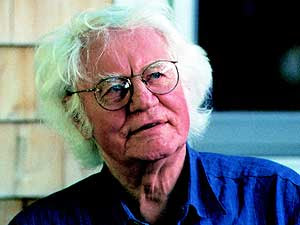

Robert Bly

By JIM GENARO

The spiritual journey from awakening to disillusionment and, ultimately, reunion with the divine, was the overarching theme of the poetry that Robert Bly shared with a packed audience last Wednesday night at UNC Asheville’s Humanities Lecture Hall.

Bly, a poet, translator and founder of what he calls the “expressive men’s movement,” presented “The Soul is Here for Its Own Joy: An Evening of Sacred Poetry,” featuring works by the mystical poets Jalaluddin Rumi, Mirabai, Rainer Maria Rilke and others. About 300 people attended the reading, which was sponsored by UNCA’s Office of Cultural and Special Events and the Prama Institute.

Before the readings from some of the world’s great mystical poets, Bly read a couple of his own poems, “because you need to know where I am before I start reading spiritual poems.” He then added, cryptically, “That’s a joke.”

The readings were sprinkled with commentaries and his repeated question to the audience, “Can you feel it?” Most poems, he read twice, emphasizing certain passages.

Throughout, Bly’s unique humor punctuated his words.

Describing his work with the expressive men’s movement, Bly said, “These men’s gatherings are ways to feed poetry to guys.” Generally, the gatherings have about 40 or 50 participants, and he noted that there is “a little bit of difference” between the sessions and a comparable gathering of women.

“One of them is that women actually learned to talk a long time ago ... but the men seem so surprised!” he joked.

Mystical poets — particularly those of the Hindu and Sufi traditions — express a very different relationship with God in their writing than typical Christians do, Bly said.

Their poetry “doesn’t say ‘I admire God and I’m a good student.’ That’s too weak,” he told the audience. Rather, the ecstatic poets say, “God is making love to me,” he added.

One common thread in their writings is the use of the term “guest,” Bly noted.

“When they use the word ‘guest,’ the aim is to make your body into a good home for travelers so that you’ll have someone living there,” he explained. “What you call ‘salvation’ belongs to the time before death.”

This implies a receptivity to the presence of God in one’s life, Bly elaborated. In the language of the ecstatic poets, this often carries sexual connotations.

“If you make love with the divine now, you will spend the next life with a satisfied smile,” he added. This concept is “a little different from the people that say ‘Yeah, I love God ... I think I do.’”

Reading from the works of Kabir, Bly said, “Between the conscious and the unconscious, the mind has put up a swing. All earth’s creatures — even the supernovas — swing between these two trees and it never winds down.”

Jokingly, he added, “The Indians are very, very open to people who say weird things, but they would be kicked out of graduate school here.”

Bly then turned to the Indian mystical poet Mirabai, who he noted was a devotee of the Hindu god Krishna.

Born into a royal family, Mirabai decided at a very young age to devote herself to spiritual matters and began seeking out holy men whose feet she would wash and then drink the water.

Her family, Bly noted, decided “this is not appropriate for a princess,” so they imprisoned her in her room. However, she would escape by tying saris — Indian dresses — together to make a rope and climbing out of her upper-floor room to resume the practice.

“It’s hard to deal with a daughter like this,” Bly joked.

As an adult, Mirabai devoted herself to Krishna, whom she referred to as “the dark one” — an apparent reference to his flowing black hair.

“Listen, my, friend, this road is a hard one,” she wrote. “If we could reach the lord through immersion in water, I would have asked to be born as a fish in this life ... The heat of midnight tears will bring you to God.”

“It’s the mood of Emily Dickinson, you know what I mean?” Bly commented. “But (she is) a little more excessive.”

In a traditional context, he noted, these poems are “always meant to be done with music — ecstatic music.”

Mirabai often expressed her longing for Krishna as sexual desire, he said.

“If you come anywhere near my house, I will close my sandalwood doors and lock you in,” she wrote of the god. In the same poem, Mirabai says that she “turns her life over to the midnight of his hair,” Bly read, emphasizing the passage.

“Now, do you see how that’s really different from Christian poems about this?” he asked. “Now, I don’t mean to say that Christian poems are inferior in that way, but there’s not a lot of hair in them,” he added, prompting laughter from the audience.

A common thread in mystical poetry is a progression whereby the poet first becomes enamored of the divine, only to experience a sense of separation and loss of spiritual awareness before later returning to that initial awareness, Bly said.

He noted that this path can be seen in many Christian writers, such as St. John of the Cross, but added that Indians seem to be more accepting of the periods of separation.

“They don’t commit suicide. They don’t go to therapy. They say, ‘I’ll be alone for two or three years. Everything in my life will be stupid and dull. That’s the way it is.’”

Bly then focused on writings by the Czech poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who he said was “the first poet that I read in the Western tradition who had something that I later would find in the Hindus.”

Bly read from a poem by Rilke, “I am too alone in this world and not alone enough to make every moment holy.”

“If we had a culture in the United States, you would hear these (verses) on the television,” Bly said. “You know, television’s going to get worse and worse, it’s hard to believe.”

Americans are so addicted to television that programming does not even have to be good anymore, he added.

“The reason why it turns so quickly is because you cannot form a thought in that time and that’s the main thing the corporations want — for you not to form a thought.”

Bly read some more of his own poems, including a couple about his family.

He reflected on his mother, who, he wrote, was the only one in the family to talk about his father’s drinking.

“And nobody wanted to be on her side,” he added, referring to his brother and himself.

His father, Bly said, was a reluctant churchgoer and husband. “One life, one woman — that was God’s rule and he didn’t like it much,” Bly read.

He then turned to the Persian mystical poet Rumi. Persia — modern-day Iran — was a great culture at the time of Rumi’s life, Bly noted.

He said he had recently traveled to Iran with his friend Coleman Barks, who was being honored for his work as a translator of Rumi’s poetry. He said that during his time there, he heard many people express great love for Americans and that he felt a strong kinship with the people there.

Tensions between the U.S. and Iran obscure many Americans’ ability to see the great historical role and intellectual culture of the Persian world, Bly said.

“We can’t admit another culture is better than we are,” he argued, but added that “the Iranians are a little nuts, of course — especially the people running it.”

Quoting Rumi on the nature of ecstatic poetry, Bly said, “What you are eating is your own imagination.”

The poet often used fairly simple images in a flowing succession that stimulates the listener’s imagination and leads back to where it started, Bly said. These images, he added, “don’t comfort you at all.”

In one poem by Rumi, which Bly translated, the mystic lists 12 lies that people commonly tell each other. These included “The one you love is unfaithful,” “Your night will never end in dawn” and “The people in the underbrush say ‘There is no path to the mountain. And what’s more, there is no mountain.’”

The last of these lies was that nothing is communicated without words.

Addressing this, Bly said, “Once you love communication — which you learn with words — you’ll realize that it takes place without words.”

No comments:

Post a Comment